How to Build Better Cars? Make Them Adaptable

The problem isn’t just in the product, it’s in the way we are producing them.

If humanity is to plan for the future, then it’s also up to people to try to predict it. But prediction is a tricky business.

Back in 1972, an influential academic organization, the Club of Rome, was formed to address major global challenges. To quantify the challenges that lay ahead, this group of intellectuals and business leaders, partially funded by the Volkswagen Group, ran computer calculations based on contemporary trends in consumption and population growth. The conclusions were published in the landmark book, The Limits to Growth, with this infamously sobering prediction: By the year 2000, the world would run out of resources, and millions would face starvation and death. The study concluded that the only solution was for human civilization to consume less and aggressively throttle back industrial progress.

Of course, the prediction, as well as its prescription, has never materialized (though it did help lay the foundation for the modern environmental movement). What the study failed to take into account was the ingenuity of technological advances and improved efficiencies that have allowed industries not only to sustain themselves but also to thrive in the face of resource challenges.

Where did the study go wrong? It ignored the lessons of the environment it was aiming to protect. Evolution has long taught us that nature always endures by altering its design system.

But this process, as applied to technology, has gotten us only so far over the past 50 years. We’ve successfully put off the Club of Rome’s prediction, but there’s no denying it still has resonance.

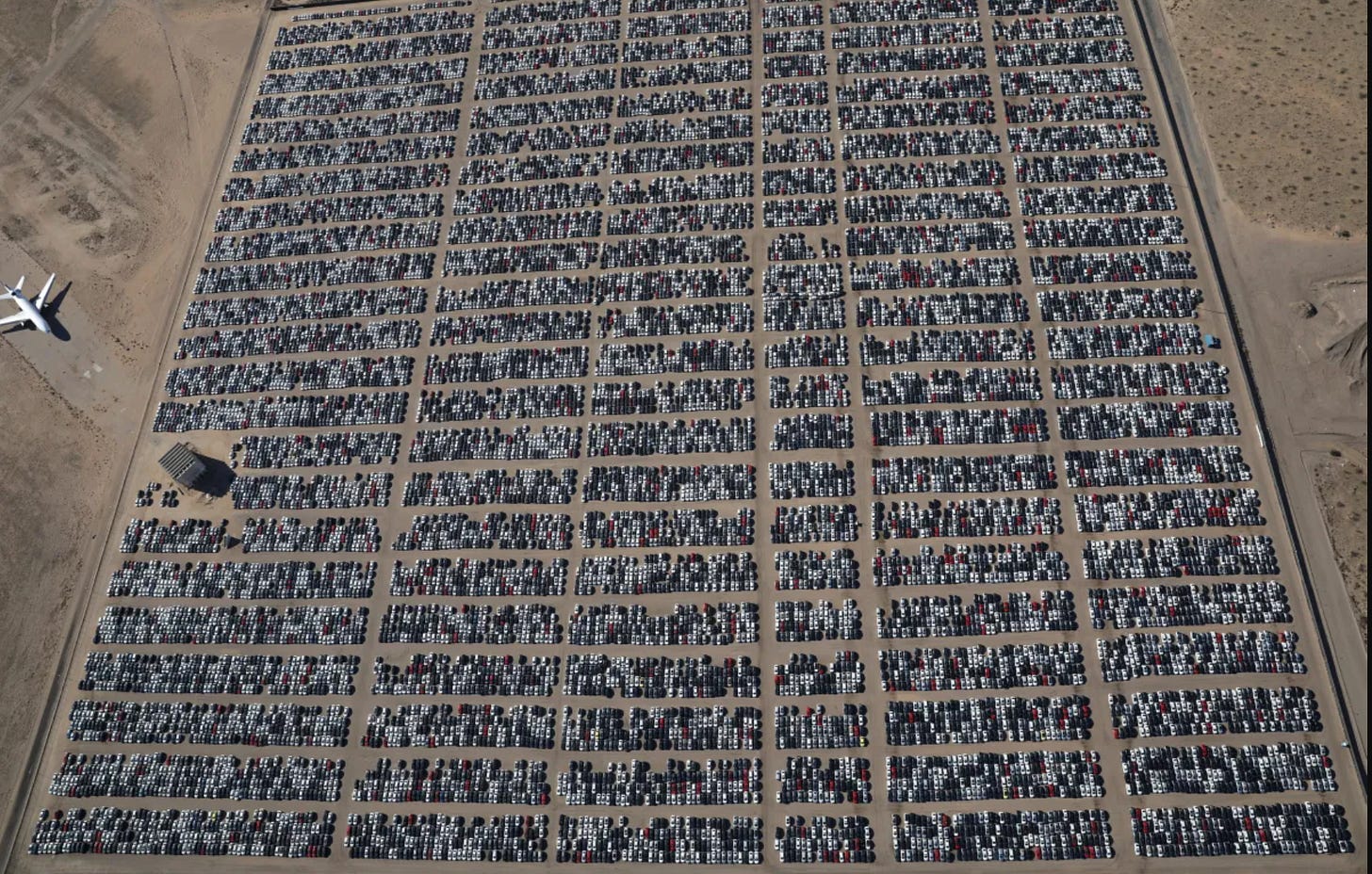

For far too long, we have accepted that the “death” of our physical products is the inevitable price of progress, akin to “survival of the fittest.” Yet this trend, particularly in the automotive world, has culminated in record ownership costs, recalls, and the price of new models growing out of reach for the average consumer.

Our vehicles are stuck in time as they serve their singular purpose, their lifespan limited by the failure of individual components and spiraling depreciation. How many millions of consumers have been forced to buy a new vehicle because the cost of a repair was more than the value of the entire car? Our landfills and junkyards are vast wastelands of industry’s shortsighted practices.

By now we know that planned obsolescence harms the environment and fosters distrust in consumers. Not only that, it’s unsustainable.

How do we stop the madness?

By returning to the lessons of nature and discovering there’s even more to apply. Evolution is not just adaptation at the expense of life itself. Nature is far more masterly than that. Take gray wolves, for example. Though mainly known for being carnivorous, when their meat sources decrease, they don’t die off. Instead, they can “retrofit” the chemical makeup of their stomachs and shift to a plant-based diet. What keeps them going? They naturally have an ongoing capacity to adapt.

It’s an elegant solution, and in technology, it’s easily applied to software, where downloadable updates offer almost seamless ongoing improvement.

But what about hardware? At Delise Automotive, we are convinced the solution applies there, as well. We reject the old paradigm of simply moving on to the new model while treating the old one like trash. Instead, we are designing products that can be updated while still retaining their core value.

We’re not just building cars. We’re creating an active industrial ecosystem that can integrate infinite possibilities to make a car improve over time.

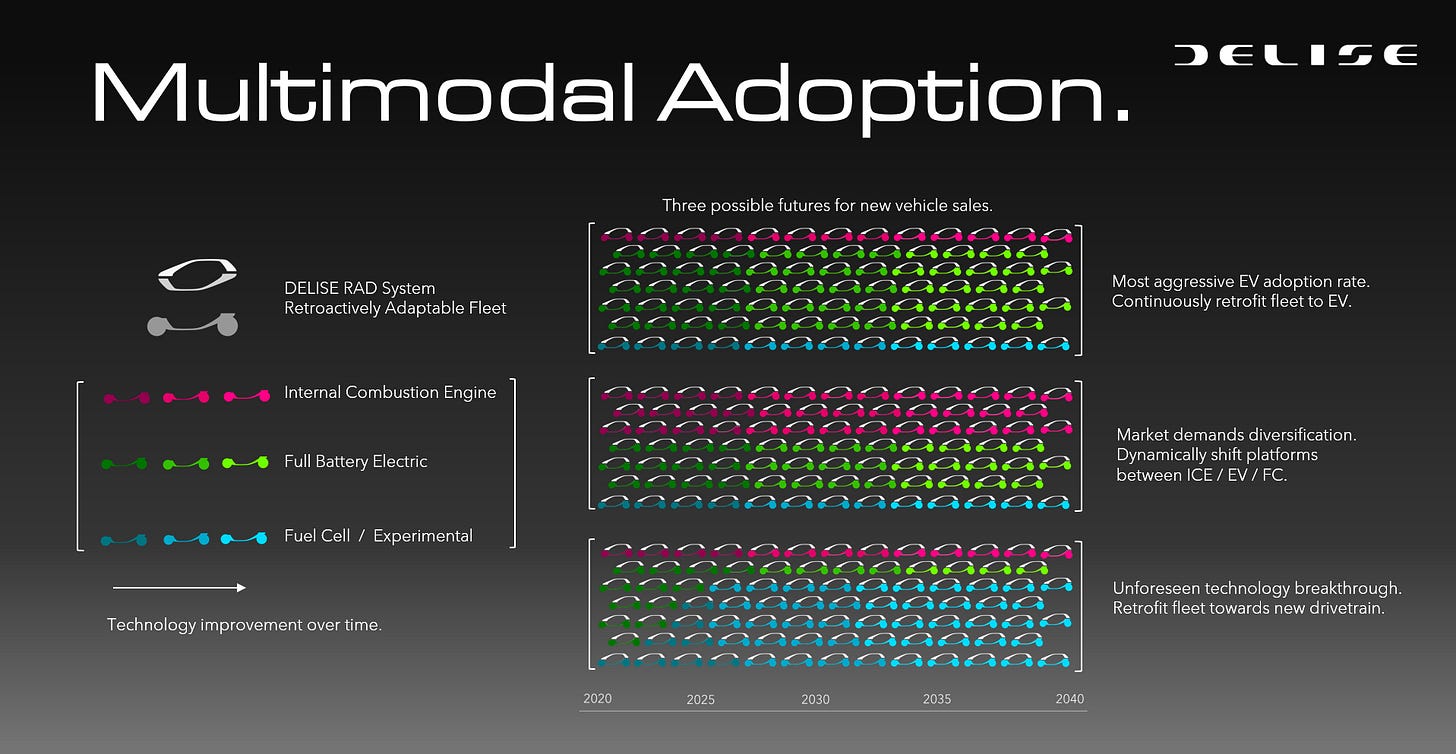

We call this approach Regenerative Adaptable Design (RAD).

With a combination of modular-design principles, we can swap out and recycle old parts while the core is maintained, thus expending fewer resources. This isn’t repair. This is new product life through adaptation. With RAD, the result is an improved and refined car that can once again be ushered into the future.

With RAD, consumers become active participants in the sustainability of the products as they enjoy longer-term value. An alternative business model supports both profitability and the longevity of each unit. Granted, initial capital investment is high, but we can show that long-term advantages more than recoup the costs.

What does RAD look like?

We’ve already gotten a glimpse in the aerospace industry, where single-use modules were standard practice for decades, making the field cost-prohibitive for private-sector business to enter. Designing reusable rockets was a challenging feat, but their value has proven more than worth the cost. The SpaceX business model has reduced the cost of launching payloads by billions of dollars.

What would RAD look like in the auto industry?

Delise Automotive is now designing it with the goal of realizing it: a car with the ability to regenerate; a design driven by residual value and long-term quality; a business model with as much adaptability as the product itself.

In the coming weeks, we’ll be giving you a revealing look into how we are developing this ethos into a fully functioning proof-of-concept prototype series.

We’ll also be answering your questions, giving you an insider’s view of our operation, and building our case for a future that we can’t wait to take a lead role in creating.

COMING UP NEXT: The “mobility movement,” which promised equitable and efficient transportation for all, is all but dead. Why it has been doomed to fail.